Fedora 14 64-bit Flash Problems

Its rather old news, but rather new to me. There is a known bug with the 64-bit Flash plugin when used in Fedora 14. When playing back certain Flash videos, the bug produces regular high-pitched beeping noises, as though there is some odd clipping issue. The culprit of the bug is a recent upgrade in glibc's memcpy(). I'm seeing a few hacks and patches being thrown around in the bug report, but for now, I'll probably just stick to running 32-bit Flash in a wrapper.

And again, here's the bug report.

Mirror, Mirror, Who’s the Oldest of Them All?

I'll admit, that my Arch updates haven't exactly been occuring with religous regularity, but I never allowed more then a month at most to pass between full system updates on my Arch machines". But today, when I decided to do a full update I was surprised to find that all my packages were already update. Especially since I remember seeing the same message on the last update. Some digging through my log files revealed that the last time one of my system updates actually updated something, was in August of last year. Which means that four months have passed without my system actually being updated. Oh sure, I issued a system update command pretty regularly every few weeks, but no packages were ever updated.

This is Not Good.

Some more digging was required, and it was revealed that the mirror I've been using, mirror.cs.vt.edu/pub/ArchLinux, hasn't been synced to the Arch repository in a very (very) long time. This is also Not Good. But perhaps even more worrying then Virgina Tech's laxness, is my laxness and unawareness. How could I have not notice that various programs on my laptop were several versions old, or that my system upgrades were never doing anything!

So I am doing a massively huge upgrade right now, and I fully expect it to wreck serious hell on my system. But at least that's better then walking around completely oblivious to the various known security holes on my laptop.

Me and Tex

Someone once told me that all the "cool kids" use Latex to write up all their technical documents. Due to my desperate desire to be part of the cool crowd, I immediately began reading through Latex tutorials. At the time, the only formal document I was working on was my resume, so I rewrote my resume in Latex, and because I wanted to have lots of fancy formatting, it took me a surprisingly long time to write it up. The end result was a resume that looked pretty decent, and one very annoyed college student who decided that Latex was far too aggravating to be used on a regular basis for such trivial things like lab reports or resumes. So for the longest time, my resume was the only document I used Latex for.

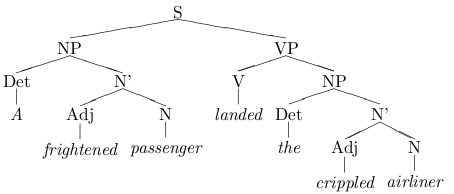

Now lets put the way-back machine in reverse and jump forward one year, to last week, when I was typing up my linguistics homework in VIM. We were working with sentence trees (think back to your automata/algorithms class, where you used a formal grammar to show that a string is an element of a language) and unfortunately, there is no good way to draw graphs, or much less trees, in plain ASCII text. Lucky me, Google-fu revealed that there are numerous Latex packages that will allow a writer to knock together some pretty spiffy graphs. Long story short, it took me a really (really (really (really))) long time to write up my linguistics homework using Tex. I was up till 4 AM, and most of that time was spent making sentence trees. Granted, I spent a pretty good chunk of time relearning Latex, learning how to use some crazy packages I found out in the Internet, and going "Ooooo! Look what I can do!"

Ooooh! Pretty tree!

The end results: the loveliest homework assignment I've ever turned in, and one tired college student.

Funny story, the next day, I wrote up my algorithms homework in Latex. This week, I wrote part of my circuits lab report and my new linguistics homework in Latex.

I run Linux almost exclusively and its often quite difficult for me to create nice looking documents with fancy charts, tables, and nicely notated equations, because quite frankly, Open Office just doesn't cut it when I need to make stuff look nice. Not only that, but I still haven't bothered to install Open Office on my laptop. The end result is that I write most of my lab reports in Microsoft Office on the school computers. Now I'll admit, I do bash on Microsoft on occasion, but I actually enjoy using Microsoft Office 2010. Office's new equation editor is simple to use and it creates really pretty looking equations, and the graphs now have nice aesthetically pleasing colors and shadows (unlike the old-school graphs). So really, there hasn't yet been a reason for me to seek out an alternative to MS Office. Until now of course.

Latex allows me to create epically awesome, professional grade documents in about the same amount of time as it takes in MS Office. Some tasks are actually faster because I don't have to fight the editor program, which usually thinks it knows better then me. I can now also work on my documents from the comfort of my own desk, or on my laptop while I'm chilling in the hallway between classes. Plus, documents marked up in Latex just look better in general then your typical MS Word doc, due partially to more consistent formatting rules and a more structured layout.

So join the rest of us cool kids! Jump on the Latex bandwagon! After all, how could something created by Donald Knuth possibly be bad?

My Time with Arch

I've been a proud and content Arch Linux user for a little over one year and nine months now, far longer then I've spent with any other Linux distribution. Arch put a happy end to my constant distro-hopping lifestyle, and I've been so pleased with its simplicity and performance that I've spared nary a glance at any other distribution over these past 21 months. But in more recent times, I've been having some disagreements with my Arch system and so I've slowly started reverted to frequenting the old haunts of my distro-hopping days (i.e. distrowatch.com, and other such distro news sites).

Stability has always been a much touted feature of Linux in general, but some distributions lay a greater claim to that attribute then others. Arch in particular has tended to be slightly more bleeding-edge then other distros, sacrificing stability for the newest features; packages are updated in the repository as soon as new versions are released and with a relatively minimal amount of time (extremely minimal compared to other Linux distros like Debian) spent in testing in an Arch environment, just enough to ensure that the packages don't completely break the system. While this strategy has its benefits, namely that it allows users to get the latest and greatest software right when it comes out, it comes at the cost of stability (and security to some degree). And the more packages that I've added to my system, the more I've started to notice just how unstable Arch can be.

I generally run "pacman -Syu" to do a full system update at least every week, and I try not to let my system stay without an update for three weeks at the longest, so in general I'll stay pretty well up-to-date. But it has not been uncommon, that after performing a full update, that my system completely locks up or goes completely nuts. Take for example, just a few weeks ago, when a full system update made my Arch Linux partition completely unbootable and required that I boot a live CD and futz around in the configuration files. When my laptop was finally usable again, I had to mess around some more with my wireless drivers to get them working again. And lately, after my most recent system update, I've been having some problems where my laptop will occasionally freeze up and become totally unresponsive to everything except a hard reboot, and system logs show no behavior to be out of the ordinary. Of course, not all of the breaks in Arch have been this bad. About four months ago, a system update made it so that I could no longer hibernate, a problem which was easily remedied by a quick visit to the Arch wiki and a few short commands. Sadly, the list of weird errors goes on (although its not that long).

Two years ago, when I was moving off of Debian testing, Arch's bleeding edge packages were quite welcoming, but not that I've matured a little bit, I don't care as much about the latest features (Lets face the facts, the programs I've been using the most these past few weeks, have been vim, GCC, SVN, and Zoom). My first priority these days, is getting shit done. And if my laptop decides to go bat-shit-crazy now and then, it seriously hampers my ability to work properly. I don't mind a few bugs now and then, and I could probably even live with a rare kernel panic, but sometimes I get the feeling that Arch is maybe just a little too bleeding edge for me.

I mentioned earlier that another one of the costs of having the latest and greatest software, is security. A lot of the newest software releases tend to be not as well hammered out and therefore are slightly more prone to have security holes. I'm only a slightly paranoid Linux user, so while the lack of security is a little worrying to me, its not a huge deal breaker. Arch's lack of solid support for more powerful RBAC security modules like SELinux or AppArmor has also been a little worrying to me. I would love to be able to slap on some powerful RBAC policies on my laptop to give me greater piece of mind, but Arch's normally awesome wiki is a little lacking in help (although it seems that reccently, the SELinux page has gotten a little more meat to it).

This next point is a rather silly and illogical thing to hold against a distribution, but I feel that it needs to be said because its entered my thoughts a few times in the past year. Whenever I go in for an interview, I generally try to play up my Linux expereince (which is not incredible, but still fairly impressive enough). The logical question for an interviewer to ask of course, is "what distribution(s) do you use?" As soon as the words "Arch Linux" comes out of my mouth, I can see the interviewers knocking some points off of my interview. People always assume that Arch is just another one of those random "edge" distros that is basically just an Ubuntu/Fedora knockoff with some sparkles thrown in, and no maybe how much I explain it to them, I know that they don't respect an Archer as much as they respect a Slacker. So yeah, I'm a little shallow, but I do care about what people think about me, especially in interviews. A part of always wishes that Arch was just a little more mainstream and a little more well known.

So I've taken some pretty mean shots at Arch, but my comments shouldn't be miscontrued to indicate that hate I Arch. Quite the contrary in fact, I've loved using Arch. My old Arch review enumerates out more clearly the points of Arch that I really like, but I'll list them out here quickly.

- Fast! - Compiled for i686 and lightweight with no extra cruft thrown in

- Clean - there is nothing on my Arch system that I didn't put there

- Simple - things tend to be very straightforward and elegently simple

- Awesome documentation and user community - Arch's comprehensive wiki is in my opinion, one of its strongest selling points, also the forums are quite helpful.

- Rolling updates - its nice not to have do some big update every six months...

All the reasons that I first came to love using Arch still hold true, its simply that as time has worn on, I've changed a bit: I don't care as much for bleeding edge features, stability and security have become bigger issues, and I've started caring about what other people think about me. So I've been asking myself, "is Arch still for me?" And I think the answer might be no. I purchased a used IBM Thinkpad reccently, and I don't think Arch is going to be my first choice for it.

It seems like its time for Arch and I to "take a break" in our long relationship. But don't worry Arch, its not you, its me.

Smashing the Stack for Extra Credit

(So this one is a little old... I have a habit of writing up drafts, stashing them away to be uploaded later, and then completely forgetting about them.)

A quick intro to buffer overflow attacks for the unlearned (feel free to skip this bit).

I would highly recommend reading AlephOne's Smashing the Stack for Fun and Profit if you really want to learn about buffer-overflow attacks, but you can read my bit instead if you just want a quick idea of whats its all about.

Programs written in non-type safe languages like C/C++, do not perform bounds checking on memory when doing reads and writes, and are therefore often to susceptible to what is known as a buffer-overflow attack. Basically, when a program allocates some array on the program stack, the possibility exists that if the programmer is not careful, her program may accidentally overwrite the bounds of the array. One could imagine a situation where a program allocates N amounts of bytes on the stack, reads in input from stdin using scanf (which terminates reading input when it hits a newline) and stores the read bytes in the allocated array. However, the user sitting at the terminal might decide to enter in more then N bytes of data, causing the program to overwrite the bounds of its array. Other values on the stack could then be unintentionally altered which could cause the program to execute erratically and even crash.

But a would-be attacker can do more then just crash a program with a buffer-overflow attack, they could potentially gain control of the program and even cause it to execute arbitrary code. (By "executing arbitrary code" I mean that the attacker could make the program do anything.) An attacker can take control of a program by writing down the program stack past the array's bounds and changing the return address stored on the stack, so that when the currently executing function returns control to the calling function, it actually ends up executing some completely different segment of code. At first glance, this seems rather useless. But an attacker can set the instruction pointer to anything, she could even make it point back to the start of the array that was just overwritten. A carefully crafted attack message, could cause the array to be filled with some bits of arbitrary assembly code (perhaps to fork a shell and then connect that shell to a remote machine) and then overwrite the return address to point to the top of the overwritten array.

A problem with the generic buffer overflow attack is that the starting location of the stack is determined at runtime and therefore can change slightly. This makes it difficult for an attacker to know exactly where the top of the array is every single time. A solution to this, is to use a "NOP slide," where the attack message doesn't immediately begin with the assembly code but rather begins with a stream of NOPs. A NOP is an assembly language instruction that basically does nothing (I believe that it was originally included in the x86 ISA to deal with hazards) so as long as the instruction pointer is reset to point into somewhere the NOP slide, the computer will "slide" (weeeeee!!!!) into the rest of the injected assembly code.

Sounds simple so far? Just you wait....

The trials and tribulations of my feeble attempt to "smash the stack."

The professor for my security class threw in a nice little extra credit problem on a homework assignment last quarter. One of the problems in the homework asked us to crash a flawed web-server using a buffer overflow attack, but we could get extra credit if we managed to root the server with the buffer overflow. Buffer overflow attacks on real software are nontrivial, something my professor made sure to emphasize when he told us that in his whole experience of teaching the class, only one student had ever successfully rooted the server. Now Scott Adams, author of Dilbert, mentioned in one of his books that the best way to motivate an engineer, is to tell them that a task is nearly impossible and that if they're not up for the challenge, then its no big deal because so-and-so could probably do it better. This must be true, because after discussion section, I went straight to a computer and started reading Smashing the Stack for Fun and Profit, intent on being the second person to "smash the stack" in my school.

I was able to crash the server software within less then one minute of swapping the machine's disk image in, as it was a ridiculously simple task to guess where an unbounded buffer was being used in the server code and force a segmentation fault. It took me a few more minutes to trace down the exact location of where the overflow was occurring (there was a location in the code where the program would use strcat() to copy a message), but as soon as I did, I booted up GDB and started gearing up for some hard work.

Spell Check

For about the past year, ever since I got my current laptop, I have been living without spell check on my laptop. Or perhaps more correctly, I've been living without any dictionaries for my spell check engines to operate on. Some people on Facebook where surprised when I reveled that Arch's base Firefox and Open Office packages do not include dictionaries and that language dictionaries must be installed separately.

As an engineering student, I have had precious little reasons to write essays. Those papers that I did write, I generally just wrote up quickly in VIM, and then SFTPed them into my school account where I then printed them. And while I did write lab reports up in Open Office, nobody really checks the spelling and grammar of lab reports. But because I had a rather large paper to write last week, I finally broke down and installed some US English dictionaries.

Network Timeouts in C

Reccently, while coding up some P2P sharing software for class, I came across a problem that really got me stuck. (Note, that I forked different processes to handle each upload and upload.) When reading data from another peer, my peer would generally have to block until the other peer responded, since with network programming we can never expect all of our requests to return immediately. The problem was that occassionally, the other peer would decide to die entirely and I was left with a process that would block essentially forever since the signal it was waiting for was never going to come. Now the great thing about blocking reads is that they don't burn CPU time spinning around in a circle waiting for data to arrive, but they do take up space in the process table and in memory. And of course, if my blocked reading proccesses stayed around forever, it would be very simple for a malacious peer to bring my OS to a grinding halt. Essentially, what I needed was a way to make read() timeout. Now anyone vaguely familar with using internet browsers and other such network-reliant programs are probably familar with timeouts, but I had no idea how to implement it in C.

My first thought, was to use setrlimit(), a Unix function that allows the programmer to set the maximum amount of system resources (CPU time, VM size, created file sizes, etc., for more use "man 2 setrlimit"). When setrlimit() is used to set a maximum amount of CPU time, the process will recieve SIGXCPU when the CPU time soft limit is reached, and then the process is killed when the hard limit is reached. At the time, I was a bit groggy so setrlimit() seemed like a great solution, but of course anyone with half a brain (which I apparently didn't have at the time) will realize that setrlimit() is definetely not the solution to this problem. A blocking process doesn't run and therefore doesn't consume CPU time, so setting a maximum CPU time does pretty much nothing to the blocking process; it'll still keep blocking forever.

After a little bit of trawling the internet, I finally came upon the perfect solution: alarms! When alarm(unsigned int seconds) is called, it will raise SIGALRM after so many seconds, realtime seconds mind you and not CPU seconds consumed by the process, even if the process that called alarm() is blocking. I set the alarm right before I began a read() and used signal() to bind a signal handler to SIGALRM, so that when the alarm went off my signal handler could gracefully kill the timed-out download process!

GNU Readline

I reccently wrote a shell for a project in my CS class. One of the advanced features that my partner and I implmented in the shell, was tabbed completion, and in order to implemet this extremely useful shell feature, we used the GNU readline library. The GNU Readline library is a beast, and not in the good way. Its a great hulking pile of code and documentation, intended to provide a ton of features for reading typed lines. Once you figure out what all the function pointers, bindings, and generators in the Readline library are supposed to do, things become much more straightfoward, but it doesn't negate the fact that initially figuring out Readline is a bit of a pain in the butt.

The first thing I did after we were told that the Readline library could make our project easier to design, was to pop open a terminal and type "man readline". What I got was a basic summary of Readline, so in order to get the full library manual I had to resort to Google. I did however, happen to see this at the bottom of the manpage:

BUGS

It's too big and too slow.

Now if even the guys working on the Readline library think thats its too big and too slow, we may have a potential problem on our hands.

One of the plus sides of however Readline's enormity was that it does offer a whole slew of features, like a kill ring, and generators for tab-completion of filenames and usernames. It would be very nice though, if all these features could be implemented without the need for a manual that probably took me longer to read, then it did for me to code up a generator for command line completion.